INTRODUCTION

My grandparents were Japanese immigrants who came to California for work in the early 1920s. In 1942, people of Japanese descent on the West Coast were sent to internment camps by the U.S. government. Only allowed to bring what they could carry, my grandparents put their belongings into five-gallon containers and buried them on their farm in Redondo Beach. It is unknown whether they were able to recover these things after the war, or if their possessions still lay under those fields like waiting time capsules. I have often daydreamed about taking a shovel to the South Bay to find these containers and their enigmatic contents, however the mystery and the myth of this story offer me other satisfying insights about how narrative histories operate in our culture today.

This story—and many others like it, passed down as one of my few surviving family artifacts—points to critical issues surrounding the preservation and communication of narrative histories. My own family history was left incomplete over time due to cultural and language barriers, and historical, political and social circumstance. Thus the ties between what these stories reveal—and do not reveal—are intrinsically linked to greater social issues.

Retellings explores how personal stories can enhance public interactions to create meaningful experiences that link us to a past that is easily lost. A critical issue in our culture today is: exactly what information do we pass down to future generations, and how do we engage and interact with this material? Retellings meditates on these questions and also addresses new challenges for useful and meaningful personal and public documentation in this age of pervasive archiving.

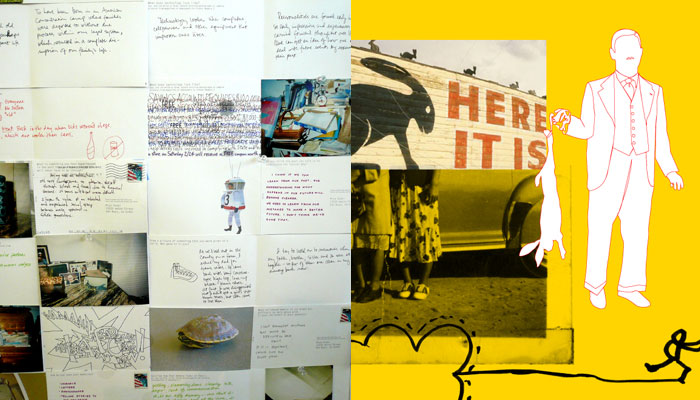

I explored design approaches to filter and craft archived material, employing different media in the interest of creating narrative spaces that are open-ended to spark empathy and self-reflection in the participants. Historically, the tradition of exhibitions speaks of collection and preservation that move toward fixed outcomes, such as with the permanent collections of museums, universities, and libraries. The crafted narrative experiences explored in Retellings are not intended to replace existing practices, but rather situate themselves alongside these more didactic methods in order to add dimension and depth. This project is invested in sparking multi-sensory responses in participants, while resisting their passive consumption of information.

Here|there is a case study in the form of an exhibition which offers personal entry points into the larger, often challenging, subject matter of displacement and immigration. The content draws upon a collection of material about my maternal and paternal grandparents’ immigration to the United States explored using design and research methods such as visual experiments, form and material studies, language explorations, and interviews. Using storytelling as a primary device, here|there acknowledges the relevance of an individual experience within a collective history.