IMAGINATIVE APPROACHES TO ARCHIVED MATERIAL

As Bruce Sterling writes in his book Shaping Things: “Design thinking and design action should be the proper antidotes to fatalistic handwringing when it comes to technology’s grim externalities and potentials for deliberate abuse” (3). In today’s hypermediated world, an explosion of information has resulted in the emergence of untold stories of great value and potential. There is an opportunity for designers to address how to filter and make meaning of this vital information to keep it from becoming lost and inaccessible.

Through our broadened networks we have become more comfortable with expressing ourselves publicly—sharing our information, opinions, and stories in public narratives—and we have benefited from this expansion of knowledge and experience. Yet the rise in user-generated content has also lead to a so-called confessional culture of blogging and YouTube, which is frequently more concerned with publishing the moment than retaining the past. We are thinking more in terms of the present, the “now,” which risks resulting in a disconnect with the past and future. How can we bridge these gaps?

Database visualization projects offer ways of dealing with a body of information in virtual form. One such project is by Jonathan Harris. His project Universe uses the metaphor of the constellations in the night sky to deal with the vast amounts of information on the web–as people made sense of the world by overlaying mythologies upon the stars, his system allows people to make sense of the infinite amount information available on the web. His work is also inspiring for its use of story and narrative, which is also demonstrated in his project We Feel Fine, which weaves together quotes from blogs to create visual narrative landscapes. Harris’ desire to bring emotion to the web is compelling. His humanizing, poetically designed interfaces transform collections of information from the web to offer personal pathways to access data.

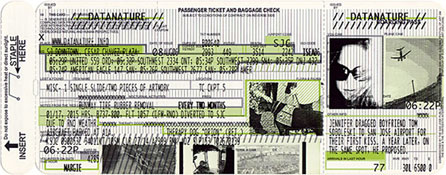

Another example is by Shona Kitchen + Ben Hooker called Datanature 2006. Kitchen and Hooker offer a unique approach to working with an archive of content: live feeds and databases that record the environment around the San Jose airport. A multi-site installation then gives a reading of this environment. The system takes imagery and prints it out on a boarding pass that features a collage of environmental elements and invisible infrastructure captured at a particular moment.

However, both of these systems deal with synthesizing real-time information. How can we design historical material in similarly humanistic, empathetic ways? I am interested in designing for the spectrum of experiences, not just for the present and the future, but to include history and the past as well.

Designer as maker of artifacts

To create more imaginative approaches to archived material, my design research explored how to push the project beyond the obvious. Lisa Grocott in her essay “Speculation, Serendipity, and Studio Anybody” makes a case for affording space for exploration, experimentation and a fluid design process in a commercial practice. Her argument is in support of a design process where designing the artifact constitutes the research methodology (4).

In this case study, I was documenting on my own family’s history, which posed interesting issues–the complexity of my family’s history was affected by language and cultural and political circumstances. The collection of material to which I had access was small in quantity and scope. In some ways this was restraining, but it also provided opportunities to focus on specific methods and explore the content from various angles. Particularly of interest was how to represent the material in a manner sensitive to the fragmentation, absence and gaps in the content (which speak to the nature of history, memory, and the past on a larger scale). Finding specific approaches to deal with the absence of artifacts became important, as well as exploring ways of dealing with these historical issues and understanding other people’s perceptions of the past.

The goal of my design research was to look at the documentation of my grandparents during the time period of their immigration to the U.S. (1915-1960) and pull out the resonant particulars from that small body of information. Experiments and visual exercises–such as form and material studies, drawing interpretation, and information design–were explored. I used interviews and probes to understand the content in a more humanistic way. Using design as research, pathways emerge that pushed back against what I thought I knew or expected, to discover spaces and different ways for this information to “live.” Instead of only being used to inform the design process, these explorations became equally important as content in the final outcome, such as the ink drawing interpretations in the case study, narration of the stories, and 3D form explorations.

Representing the intangible

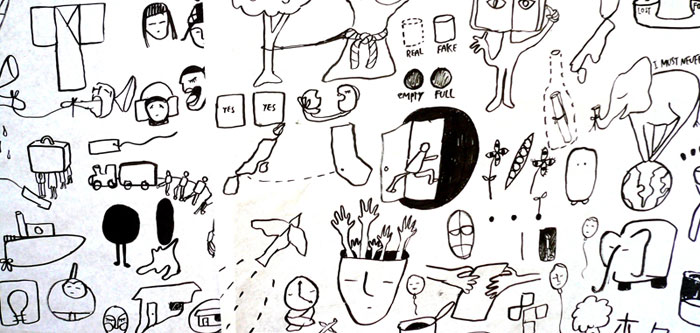

Drawing was used as interpretive tool to deal with the complex nature of the content. Originally intended to be used as a thinking tool, drawings were made in ink and paper, using both text and image. The drawings serve multiple purposes in the case study. First, as a way to get at the material—thinking through making. These studies enable a wide-ranging exploration of the content that goes beyond the physicality of the artifact/object, to visualize abstract concepts and intangible experiences. Secondly, they operate as a conceptual tool. The story themes that I extracted from the drawings had a significant impact on the design of the here|there exhibition.

The drawings were completed quickly within ten minutes,

one 36” x 30” sheet a day for a week, to encourage a free flow of ideas.

The “artifacts” that emerged from this imaginative approach were a significant part of the case study. For example, interviews were conducted with family members and then transcribed. The drawings were used to interpret the transcriptions and help to visualize and grapple with compelling ideas, questions, and words. They were also juxtaposed with the photographs, transcripts, and documents to pull out similarities and differences. For example, a drawing of a passenger train was combined with an official letter and photograph documenting my grandfather’s immigration status in the United States. The images began to speak of travel, journey and migration, and thus I began clustering other images and texts around the idea of passages. From exercises and observations such as these, four narrative themes were developed: passages, dreams, identity, and home. The themes were used to help further organize content and were used as a structural device in here|there.

Drawings in the context of the here|there exhibtion, juxtaposed with text and image

Instead of using the raw video or audio from the interviews directly in the exhibition, I chose a labyrinthine path of iteration and interpretation. Stories were reconstructed from the conversations, photos and documents. The stories were then recorded as audio tracks narrated by four different individual voices for the exhibition. This reveals a process that is not just about presenting existing material, or even about turning the material into “designs,” but rather massaging the content into a communication tool—a retelling of an historical story in a contemporary voice.

Making the historic relevant for today

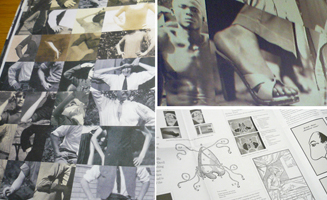

Most of the archived material available to me from my family was historical—black and white photographs and yellowing documents. To communicate these stories in a manner that would have a contemporary impact, I wanted to use current vernacular in the design of the exhibition, for example, deconstructing the images by cropping out backgrounds, posterizing the images, and using silhouettes. Visual and material explorations were used to push the content beyond the historical, sepia-toned, nostalgic elements allowing the image to be unhooked from its original context and placed in new situations for more open-ended interpretations.

An experiment combining imagery and an official U.S. government stamp

found on the back of my grandmother’s photographs.

In the beginning, I was apprehensive about toying with these historical artifacts because I perceived them as precious objects and by altering them I would diminish their power. However through cropping and isolating elements in the photographs, making dynamic arrangements, juxtapositions, and clusterings, fresh read of the imagery emerged that allowed me to strip away some of the nostalgia, reveal new relationships, and bring in an unexpected openness to the imagery, which relieved my previous hesitation. An image of the family standing in front of a house where the people have been silhouetted in white offers a variety of interpretations. Was the family erased? Are they ghosts? For example, one viewer remarked about the aforementioned image of the house that it made her want to insert an image of her own family into the exhibition. While I recognize that this kind of interpretive approach is not appropriate for all situations (the preservation of artifacts in their original form serves a very significant function), the approach offers valuable alternative ways of looking at historic material, in turn, broadening the discussion. It is my intention to provoke conversations with these interpretations that resonate with participants.

Things I looked at dealing with historical imagery, juxtaposition,

new contexts: Martin Venezky, Museum of African Diaspora,

Cabinet magazine.

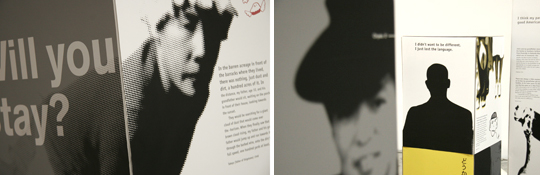

In the here|there exhibition, these approaches were applied to the design. Multi-paneled boxes enable a variety of perspectives and dynamic landscapes. Imagery and language juxtapose and intertwine at every turn of the corner, creating a push and pull between the two. Lists and questions pulled out of the context of the official documents (speaking to their origin without direct reference) propose deceivingly simple inquiries to the participant (“Reason for visit?” “Are you an alien?”). The words next to images of my grandparents speak to one another. Across the exhibition, an image of a young bride is juxtaposed next to the image of the same older woman as housewife. These juxtapositions allow us to catch the discontinuity and leaps in time and bring together disparate elements that help to create our own scenarios and explanations. They are an invitation to inspect the patterns and rhythm of life and encourage us to fill in the gaps with our own imaginative meanings and endings.

In the home gathering, the words “Will you stay?” moves around to an image of my grandmother

looking up from her sweeping, and the boxes are transformed into her front porch.

The use of audio was another way of exploring the historical material in a contemporary way. The stories are narrated by younger voices, instead of using clips from the original interviews, which creates a tension between the past with the present. One participant commented that while she was aware that the storyteller was not that of the person in the photograph, the juxtaposition made her to think of what the relationship between the voice and the image might be, ultimately evoking memories of her own childhood relationships. I also discovered that the narrated voice was also not enough to draw in the attention of the listener, so music was also composed to enhance the narration and create a particular mood for the stories.

Language artifacts

In

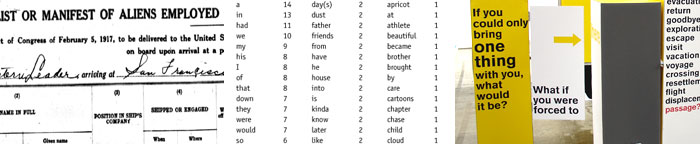

another exploration, historical and official documents (such a travel logs, passports, draft cards), along with interviews and primary research were looked at in a more formalized manner. Dates, names, words, places were pulled out of context and re-sorted in lists to expose patterns and particulars. The play on words and the crafting of language became a design strategy—often double meanings emerge, particularly when juxtaposed with images, alluding to larger concepts and creating a tone for the exhibition that is, ambiguous, sometimes humorous, sometimes ironic. A panel with an image of a young boy reads “loyal legal American” and turning the corner, the adjacent panel reveals the prefixes “dis,” “il,” and “un” which changes the read of the original statement to “disloyal illegal unAmerican.”

These word studies inspired the use of language in the here|there exhibition

as they appear in the lists and questions on the exterior of the structures.

The outcome from these imaginative approaches had a great influence on shaping the exhibition. What I was able to recover was a different kind of story built upon strategies such as language, voice and movement, as well as techniques such as juxtaposition and scale, took precedence over the presentation of physical artifacts. Designer Geoff McFetridge writes, “The trick is not the things themselves, but it’s the relationships between things that say intangible things” (5).