PERSONAL ENTRY POINTS INTO LARGER ISSUES

In her essay “My Disillusionment in Russia” written in 1923, Emma Goldman stated: “Real history is not a compilation of mere data…it is the personal reactions of all the participants and observers which lend vitality to all history and make it vivid and alive” (13). Goldman asserts that history only gains authenticity through the inclusion of multiple voices and expressions. Storytelling is a common feature in our media-saturated environment, from Google Earth to Storycorps, Ken Burns to Ira Glass, to the confessional nature of blogging to the building of brand experiences. The ubiquity of story in our culture reveals an opportunity to broaden the presence of story to explore modes that move beyond conventional video clips and voiceovers.

Communicating a collection of stories necessitates thinking about not only what an individual’s relationship to this material might be, but also how the personal nature of the material poses the challenge of making subjective content interesting and accessible to a wider audience.

Emergence of story

How do people make stories out of things (events, objects, memories) and how can design inspire people to think about the past? How do we resist the habit of generating information for passive consumption. How can we activate content based on personal experiences? Rama Gheerawo from RCA, in speaking about empathic research, talks about designing based upon individuals’ needs rather than defaulting to general observations. Gheerawo asserts that the next step is to find the deeper level of engagement (emotional, cultural) searching from points of inspiration rather than facts (14). Finnish designer and researcher, Tuuli Mattelmäki, explores empathic and more emotional, subjective approaches to design. In a recent discussion with her, we discussed that while much of this research surrounds product design and user experience, we talked about how storytelling projects and empathic approaches could be used in other contexts such as knowledge sharing or presenting design research findings (15).

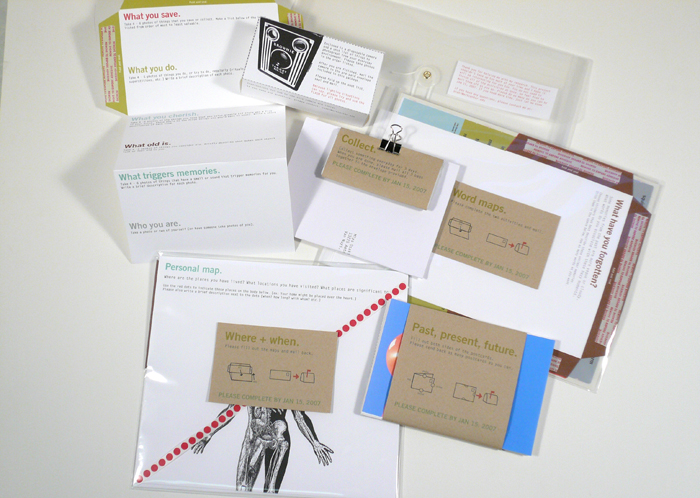

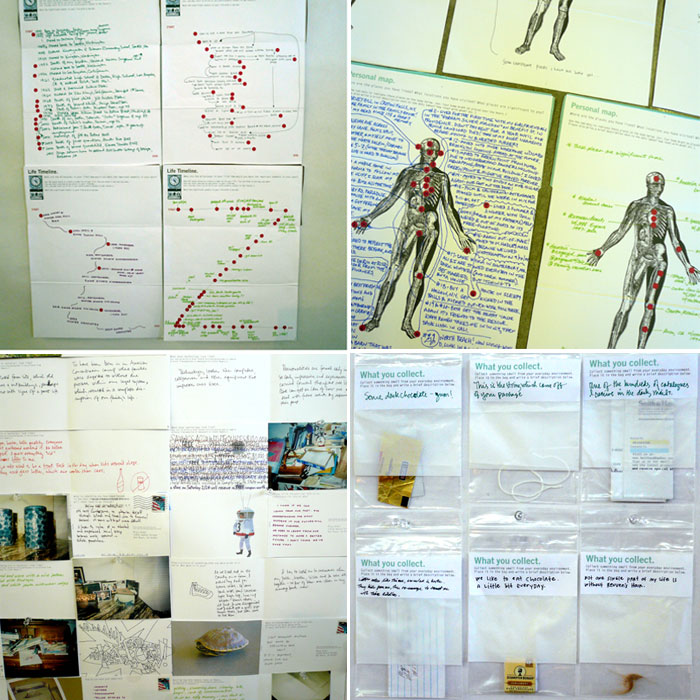

To explore these areas, I designed research kits, sending them to a small group of family members and volunteers. Consulting family members was important for providing living memories. With only four living relatives from the generation before me, it felt particularly critical to consider their reflections.In addition, limiting the case study to a small selected group allowed me to focus and explore the material. The goal was to gather personal insight about history, the past and the transmission of information between generations. The kits were patterned after "domestic probes" developed at RCA by Bill Gaver, activities designed to inspire and allow for unexpected outcomes and “provoke inspirational responses” (16). Questions such as “How do you save your memories?” and “What is something that you would want or do not want to pass down to your children?” were paired with evocative imagery on postcards. A photo survey with a disposable camera encouraged participants to capture more "intangible" things, like tactile sensations, smells, sounds, or memories through images.

Research kits included five activities (top), completed responses from participants (bottom)

The activities offered multiple levels of interpretation that provided me with a central tone for the case study. The responses revealed personal stories that touched upon the ephemeral nature of history, the fragmentation of memory, and disconnect with the past, concurrently revealing a glimpse into personal responses. One question asking "How do you save your memories?" one participant answered, "I used to write on my hands and arms. If I don't either put something down on paper or tell it as a story constantly I'll start questioning whether it actually happened. If left alone too long, I may disbelieve my own existence." These stories were at times humorous, quirky and idiosyncratic, which was invaluable in the design of the exhibition.

Anecdotes that emerged from the interviews piqued my interest and had particular resonance for me. They were often the most enjoyable, memorable and poignant parts of the interviews. While names and dates were recalled with less accuracy, anecdotal stories were remembered and recounted with much clarity. My attention was drawn to the more unusual memories: my grandmother chasing jackrabbits down on foot in the fields where she lived, or one about two sewing machines lost during WWII. Combing through the interviews, I let these unique pieces of information shape the content and tone of the case study. Little personal details, themes, moods, metaphors, such as rabbits, silence and secrets, were integral components of the exhibition. Paradoxically, as the information became more particular and specific—highlighting idiosyncratic details and moments—the anecdotes began to resonate universally. Participants responded keenly to these details which tapped into their own memories.

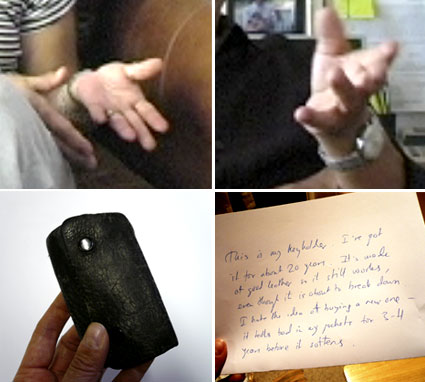

An experiment with Media Design students to explore the relationship

between objects and the past: A small group was asked to write a brief description

of an object that they considered “old.” While I was expecting to receive short

descriptions of each object, I was surprised that many of the respondents told detailed

stories about the origins of the objects and their relationships to them. These

narratives in combination with the object began to activate the material. It became

evident that anecdotes communicate history, both personal and universal.

Working with storytelling

Existing projects and design approaches that bring personal experience into the public realm include: Todd Presner’s Hypermedia Berlin project, The Museu da Passoa (The Museum of the People) in Brazil, and Local Projects, a design studio in New York City.

Hypermedia Berlin, Museu da Pessoa, Local Projects' Memory Maps

Hypermedia Berlin examines the history and culture of Berlin and its relationship to geographic place. It asserts that history is always a subjective history, organic, and changing because of how we construct and perceive our sense of place, time and information. This project reveals the relationship between place, time, and information. An interesting aspect of the project is how it is open-ended in how it is used. In a recent discussion with creator Todd Presner at UCLA, he stated that his intention was to build an online textbook, that he was surprised and satisfied with the multiple outcomes the system spawned creating new contexts that have now expanded to allow for user-generated content, including the collection of stories (17).

Museu da Passoa or The Museum of the People seeks to reveal the history of Brazil through the collection of the stories of every person in the country, utilizing a particular methodology for collection, preservation and access. Karen Worcman, the director of the museum acknowledges, “It may be that the most important factor of the digitization project is not the creation of the ‘digital collection’ as such, but the group's engagement in the process that motivates new generations to value their history” (18). Thus their methods involve designing recording installations that present as well as collect the stories, and publications that synthesize and share these experiences long-term.

Local Projects is a design studio that focuses upon three areas: collaborative storytelling, environmental media, and innovative interfaces. Their designs facilitate the collection and presentation of large-scale public interactions. The project Memory Maps (2001), collects the personal stories of a neighborhood through a human-scale map where participants leave handwritten messages and stories. This collection system becomes a physical interface to access and experience the neighborhood stories.

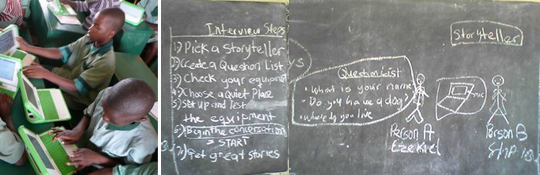

My interest in personal stories and documentation was inspired in part by a recent internship at UNICEF during the spring of 2007. There, I worked on a project called One Laptop Per Child ($100 Laptop) building collaborative wiki-based learning tools for the XO laptops that would be delivered to classrooms in developing countries. Storytelling was one of the primary strategies we used for encouraging the students to participate and create multimedia content relating to their own experiences. For example, instead of presenting them with facts about the environment, we asked them to about tell their own stories about their communities using different media, such as photo journals and how-to essays, which empowered them to actively use the system.

My background is also in independent music where I worked within D.I.Y. (Do-It-Yourself) communities. These environments embrace the voice of the individual and value the contributions of personal experiences to a larger collective. The sharing, exchange, and building of ideas—in a more open-source network—has equally influenced my interest in looking at the juncture between individual experience and public knowledge.

The use of voice

Four themes emerged from the drawing studies that revealed a relationship between the personal and the larger concepts. Each of the story gatherings contain audio, imagery, and text reflecting concepts that relate to each of these themes.

Passages: migrations, movement, pathways, relocation, getting lost, enter/exit

Identity: loyalty, power, communication, citizenship, culture, fragmentation, looking inside

Home: family, comfort, obligation, childhood, conflict, sitting and listening

Dreams: aspirations, goals, hopes, achievements, secrets, disappointment, discovery

These themes evolved from highly personal stories of my family, yet they indicated broader social issues like displacement. In order to present the tension between the personal and universal, here|there utilizes statistics about displacement (relevant to each story gathering theme) alongside first-person quotes from the stories.Thus, for the exhibition, the concept of multiple layers of voice was employed as a strategy to synthesize the content. Three forms of voice appear: the graphic voice, the audio voice, and the group voice.

The graphic voice

To merge the universal with the personal, different typefaces were used to distinguish specific modes of voice. The universal voice is presented in large, bold sans serif type and addresses the participant directly—posing questions that draw the participant in to the content via a sense of the personal realm. The questions also guide the participant towards a quieter personal voice presented in smaller texts—where passing thoughts and fragments are discovered that might provide answers to some of these questions.

The audio voice

The audio stories are narrated by four different contemporary voices and are triggered by participants’ movements and activities in the space. The act of reading and listening to stories becomes more synergistically related. The voice of the storyteller addresses the participant in a more ambient way, filling up the space of the room and coloring the read of the graphic/text elements.

"Rabbits" from Home gathering

"American citizen" from Identity gathering

The group voice

The interior space of the exhibition is one of discovery and intends to spark conversation. A surprising occurence was how the conversations of participants engaging with other participants, layer and mingle with the recorded narrative tracks. While audio offered many challenges by way of the design and experience of the voices, this vocal overlap created another dynamic—that of invisible space filled with a mixture of live voices and recorded sounds—the group voice.

Most surprising is how these voices contribute to the mood and tone of the exhibition, which was not pre-determined, but rather came out of working closely with the material. Without making light of the issues of displacement presented, the inquisitive, curious tone of the exhibition is an interesting contrast to the dire subject matter and operates in a compelling way. For example a question such as “What is your future?” or “Reason for visit?” could be addressing the subjects of the exhibition—the fate of my grandparents’ future—or the participant in the exhibition.